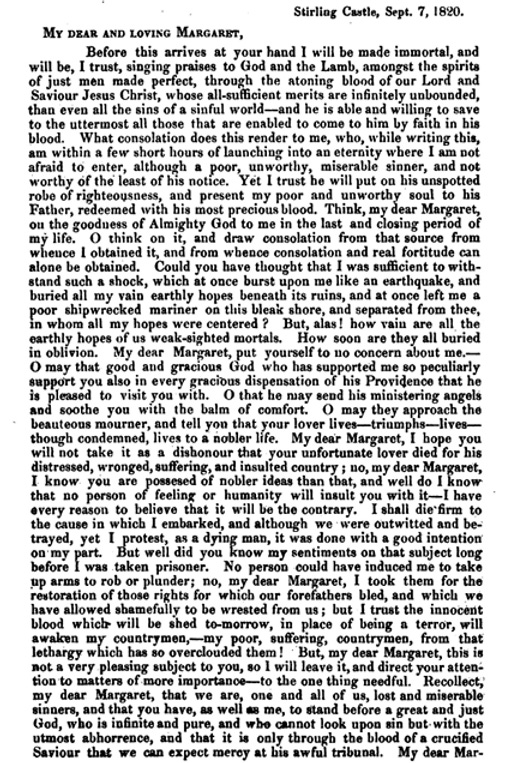

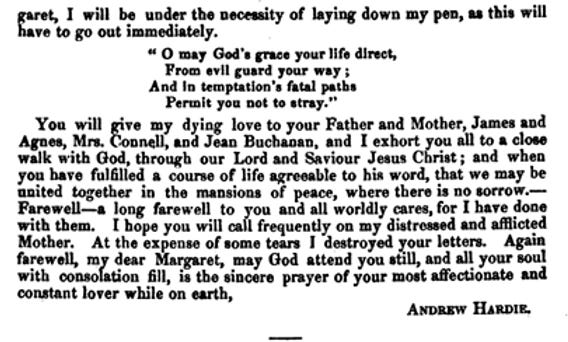

Stirling Castle, Sept. 7, 1820.

My Dear and Loving Margaret,

Before this arrives at your hand I will be made immortal, and will be, I trust, singing praises to God and the Lamb....

So begins a letter I stumbled upon while researching the dark history of the Scottish ‘Radical War’.

This historical event was pivotal to the plot my first novel, Roses in Red Wax—but on a superficial level. As I got further into writing the Darnalay Castle Series, I found I needed to know more. So I delved into primary accounts and old texts, and what I found was astounding.

So let’s go back in time to Glasgow, on Saturday April 1, 1820.

The Industrial Revolution was just beginning, and Glasgow was a city in flux. The old economic order, dominated by handweavers who worked out of their homes, was quickly being replaced by mechanized cotton spinning and weaving mills—many of which were owned by wealthy English investors. Weavers and other skilled tradesman who had always been able to provide for their families found themselves quickly sliding into poverty.

Refugees from Ireland and the Highlands were streaming into the city looking for work. The tenements were overcrowded and dirty. Typhus and other diseases swept through the neighborhoods. The old parish based education system broke down as impoverished children were forced to go to work in the factories to help feed their families.

People were angry, and the “radical” ideas of suffrage for all classes of men and Scottish independence spread through an underground network of poor and working class people.

At the same time, there was violence and unrest in the industrial North of England. The government in London was terrified it might spread.

On Sunday, April 1, the residents of Glasgow awoke to find a document, ‘The proclamation of provisional government’, plastered everywhere in the city, on lamp posts and walls. It began:

Liberty or death is out motto, and we have sworn to return home or return no more.

The proclamation demanded suffrage and independence, and it declared a general strike to begin the very next day.

But here’s the thing about that proclamation: historians today are in near agreement that it was written and posted not by radical Scotsmen, but by government provocateurs working for the Home Office in London. Their purpose seems to have been to draw the radicals into the open so they could be prosecuted.

And if that was the intent, it worked.

Within the year, three ‘radicals’ were executed and twenty more were convicted of sedition and deported to New South Wales. For the moment, the government in London had won the ‘Radical War’.

That’s the big picture history. Now let’s zoom in and make this a little more personal

Andrew Hardie

Andrew was a hand weaver.

He was twenty-seven years old in 1820. He’d fought heroically in the Napoleonic wars, then come home to find his livelihood destroyed by the factories.

After the proclamation on April 1, Andrew served as the second in command of a small troupe of Radicalized men who marched on the Carron Ironworks in Bonnymiur, northeast of Glasgow.

(Like the proclamation itself, there’s good evidence that the very idea for this act of aggression came from a government spy.)

Needless to say, Andrew was arrested and tried for treason. In September 1820, he and another leader of the uprising, John Baird, were hung, then their bodies beheaded at the Stirling Tollbooth gallows.

As he stood on the platform with the rope around his neck, Andrew defiantly declared himself “a martyr to the cause of truth and justice."

Not the happiest of endings, but there it is.

I found a collection of Andrew Hardie's letters written from his prison cell in Sterling Castle in the months before he died. As I went through them, there was one name that kept coming up in his writing: Margaret McKeigh, sometimes Miss McKeigh. He asked his mother and other family members to give her his compliments, or to let her know he received her letter, or to ask her to write to him soon.

Who was Margaret, I wondered? She was obviously important to him, but there were no letters to her included in the collection I found.

Not until until I came to September 7th, the day before Andrew died.

Margaret, it turns out, was Andrew’s sweetheart. His beloved.

I've pasted his full letter to her below, but it's not really the words he wrote that broke my heart. There's a lot of religiosity in there that doesn't resonate today.

It was the image of Margaret, alone, reading his last message and knowing her lover was already gone.

I have no idea if she attended Andrew's execution, or what happened to her afterward, but I couldn't help but include her in my novel A Radical Affair. She's not a main character, but she and her mother Agnes are present, along with another woman I stumbled upon in this research: the daughter of 'Purlie' Wilson—another man who was wrongly executed.

Purlie's daughter and niece stole into a cemetery in Glasgow the night after the execution. They exhumed Purlie’s body from his unmarked traitor's grave and brought him home to the village of Strathaven, where they buried him in his own backyard.

It's a small thing, but I'm so glad I could honor these women and their bravery by giving life to them in my story. I only wish I could reach through time and give them more.

I’ll leave you with the letter:

Curious about my work?

You can read the eBook version of ‘Roses in Red Wax’ - my debut novel and the first book in the Darnalay Castle Series - for FREE. It’s available on my website and all major retailers.

Thanks for reading History's Muse! Subscribe for free to receive weekly posts.